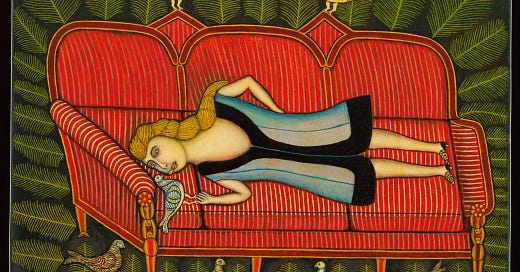

Image: Morris Hirshfield.

When I was about eleven a group of boys told me to google “dildo.” They told me it was a new Pokemon. That’s what reading My First Book, the new debut by Honor Levy, feels like. It’s like reaching into a jumbled bag of Red Scare goodies: emoticons, Catholicism, edgelord takes, transphobia. A boy notices “the they/them at the self-checkout purchasing Vagisil.” If this was the book one sampled to understand contemporary gender roles one would come away with a modernized trad view of the world. “I want to be skinny. I want to be famous. I want to be loved. In that order,” Levy writes. Well, yes. This is uwu it-girl literature.

After profiles of Levy went viral on The Cut and PAPER, I decided to dig in. It was, like the work of it-girls Ottessa Moshfegh, Emma Cline, and Sally Rooney, a sensation I DM’d friends about as I breathlessly laughed and mocked its anime-referencing, irony-laden prose. Yes, this is the book that gets a young cis white Bennington graduate a short story in the New Yorker and a throng of young girls hanging on her every word. Out of Dimes Square fame and into LA infamy, Levy has repented and provoked in pieces with her takes on feminism, the r word (I refuse to play on her turf), and reactionary politics. This regressively codependent dynamic is one view of modern gender. It’s not the only one, popular as it is. I’m sure I’m one of the people she’s trying to offend. But more than being offended, I was bored. It’s a bag of tricks without any plot or even coherent politic. It’s ambient vibe pieces rather than sharpened barbs. Throwaway lines stick out in the mind more than actual characters (“Being depressed is not the same as being oppressed”) even if hot topics come up every few pages—from “Cancel Me” to a story about a deflowered woman’s redemption from an online suitor. Levy says if she was a man, she would be an incel. That tracks. Sex seems to bore her characters more than motivate them. It’s a task they take on in pursuit of something else—usually stability, though they fail to find that too. No worries, another story, another trial. In this one, too, women are dogs.

“Maybe one day the algorithm will wake up and realize that it exists just to find nipples and it will be sad and sorry and human and pray to stop,” Levy writes in My First Book. Such poignant lines are few and far between. This brand of woman would rather be jaded than angry, depleted than desperate, drunk on their own nihilistically triumphant irony. Mea culpa. I’m just annoyed. Jealous. Petty. A woman is only good to be a vessel of projection. It goes both ways, each of us like the Spiderman meme pointing blame at the other in the mirror.

Levy’s book is only one take on femininity in contemporary literature. The girls aren’t necessarily better off in other books, but perhaps there is more nuance. In her new novel, Parade, Rachel Cusk turns men and women into mythological letters like “G,” standing in for gendered stereotypes as they try to break the silence of their roles. Like the primordial work of Sheila Heti, she rises above the fray to discuss gender in hallowed, fairy tale-like settings. Meanwhile, Levy’s closer peers tear into the transgressive possibility of degradation. Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Emma Cline’s The Guest offer two such esteemed examples. Both feature self-destructive women seeking oblivion through painkillers. In the former, a woman wants to sleep forever. In the latter, a woman is trying to survive after leaving sex work by jumping from one rich patron to another. Neither escapes their escapades unscathed. Moshfegh is a troll, committed to the bit. Lapvona is a mess. Cline at least seems to want to believe her women have an inner life, even if they are written in wide, commercial swipes.

The queen of the chic white woman canon, though, is probably Sally Rooney. Her protagonists try to seek a way out of their emotional destitution through men. Whether or not they stop cutting and vanishing into episodes of depressive bed rot, her protagonists chase love as a form of prayer. Far from the private chivalry of old, Rooney’s characters descend into the debasement of love. Normal People and Conversations with Friends attempt to ponder how healing relationships can be under the alienation of capital. While Beautiful World Where Are You? was a curious expansion of her normal themes, it also felt limited by some of its autofictional influences. While these books could easily serve as a primer on basic bitch lit, they offer a window into how the straights are doing. Not well, one might say.

Heterosexuality is being forced to rebrand. Some on the Left take a similar tact to Levy’s irony-pilled shrug-off. In a Post #MeToo world, women regularly complain about their boyfriends, as if in an attempt to absolve themselves from the complicity of the structural matrix that also benefits them. This is heteropessimism. Men are shit so why bother trying to change them? May as well just accept the limitations of their emotional capacity and use them back.

At its core, such abject heterosexuality is simply the coil of heterosexuality rebounding—perhaps straightness cannot exist without debasement. Women convince themselves this power dynamic is erotic and man must reinvent reasons he is, indeed, better. None of this is bell hooks’ vision of liberatory love found in All About Love. Many contemporary heterosexual love stories immerse themselves in the oblivion of pain as a bid to stay relevant. From Rachel Cusk’s Parade to Emma Cline’s The Guest, the breakdown of connection is far more interesting than salvation. Still, outside of cis white womanhood many writers are exploring the complex relations of race, gender, and dysfunction. Venita Blackburn, Emily Zhou, Kaveh Akbar, and Sarah Thankam Mathews all explore how queerness complicates the urge to pick at wounds while still wondering if community (romantic or platonic) might not still be possible. Mathews’ All This Could Be Different is a particularly cogent read on the possibility of repair. Of course, there are authors who poke holes in our society while still employing the gift of craft.

In a world where straight guys are kind of gay and bros fuck bros for fun, being gay is no longer transgressive, as one of Levy’s male characters remarks. Tony Tulathimutte questions how progressive our gender politics can be in his dexterous new short story collection Rejection. In “Ahegao, or the Ballad of Sexual Repression,” he writes a gay man whose sense of abject shame is so strong that he can’t have a successful relationship. He resorts to porn, requesting an elaborate narrative video from a camboy. (“Stalactites of cum should hang from your eyelashes,” he writes.) Purity is a large part of contemporary gender discourse, whether political or sexual. Few stories have this amount of cum and far fewer can pull it off in the literary scene. (The story originally appeared in The Paris Review.)

Worse is the violent shame of Tulathimutte’s story “The Feminist,” that originally went viral on N+1 for its take on incel culture. Through men, he analyzes the matrices of desire. His incel protagonist is “dragging his virginity around like a body bag into his mid-twenties.” He learns “if not feminist values per se, the value of feminist values.” He is the worst kind of reply guy, earnest and arrogant while still self-degrading. When he is turned down, he is persistent. He thinks he deserves an answer even when he’s the one who’s done wrong. Of course, he doesn’t think he’s the one who’s wrong. He’s a good guy. He has a “QPOC agender friend.”

While Tulathimutte uses emoticons and internet speak to write a dating profile in the short story, it’s riotously humorous—familiar, cringe, delirious, delicious. His writing offers a strong rebuke to reactionary politics while still offering a nuanced engagement with identity politics. The slipperiness of online performance resurfaces in each story—sometimes analyzing the same event from multiple characters’ perspectives in different stories. “Main Character” is a masterpiece, Tulathimutte is firing on all cylinders as a sly, hacking character who wants to opt out of identity politics altogether. We have few satirical writers this engaged with culture who can intelligently co-opt millennial culture in order to subvert it.

For Tulathimutte, rejection is the foundation of gender dynamics. Men leaving women, women rebuffing men, men too smart to know better but not smart enough to do better. Expectations are what keep us down. “Hell was hottest for femme PoCs who betrayed their own.”

I’m aware, of course, that I’ve chosen to praise a book by a man rather than by a woman. But such a simplistic reading flattens the work of all involved. Sometimes women can write bad books. Sometimes men can write good ones. This is why the manipulative narrator of Tulathimutte’s “Main Character” likes social media: “All the talk of bodies and spaces in a place that lacked both.” If we merely rely on rallying cries of “girlboss,” we can fail to see the traps right in front of us.

New short story, Can You Hear Me?, for Angel Food Mag.

Zooey Zephyr Profile for Teen Vogue.

On J D Salinger’s later works for LARB.

Interview with Catherine Breillat for Screen Slate.

Trophy Lives for Bookforum. (Print only currently.)

On Catalina Munoz’s show for frieze.

Catalina Ouyang Review for Document Journal.

Lux Capsule (Summer 2024, Print Only) and Drift Capsule Mini-Reviews.

Great read (Thank you algorithm), just a quick question: is Tulathimutte’s Main Character you reference out of Rejection? Thanks!

Best opening I’ve encountered in a while.