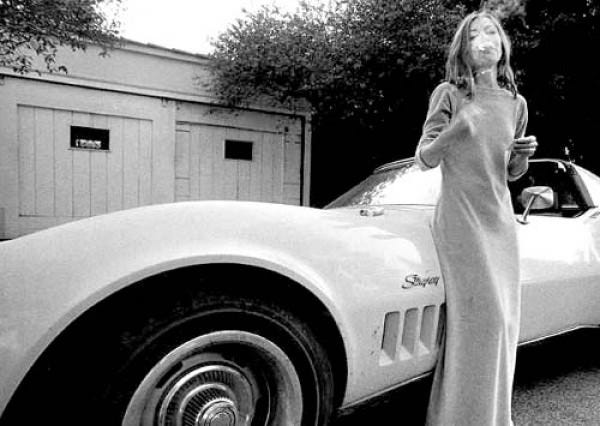

Joan Didion, smoking in front of a fancy car.

Content note: Brief discussion of rape

For some writers, the discovery of Joan Didion is a rite of passage. Reading her bold, apocalyptic prose stirs something in us. She inspires a desire to write and chronicle the present. I first read Didion in snatches before, during, and after work. On the train, in caf…