Ghost Stories

On Keith Haring, Pessimism, & Optimism

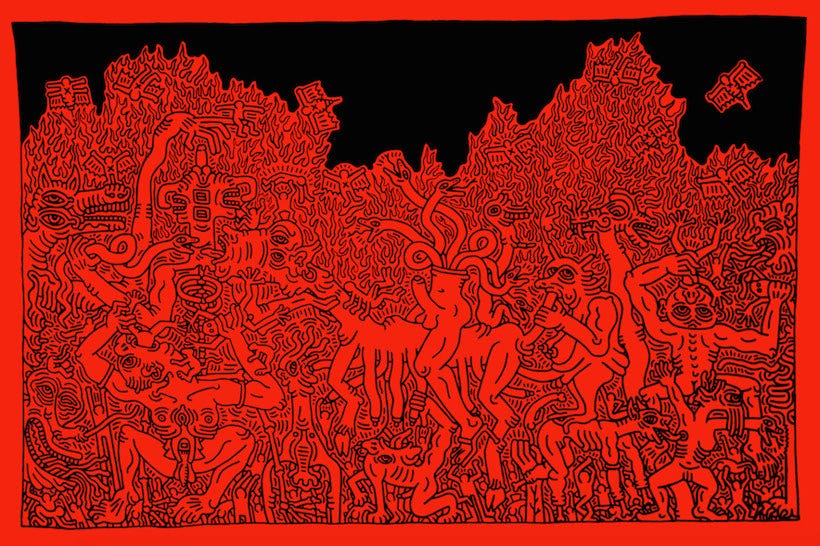

Keith Haring, Untitled (July 7, 1985) (1984), Skarstedt. A Keith Haring work depicting hell in bold red and black line work.

Near Union Square a large digital Climate Clock displays the amount of time left before a critical window closes in the fight to avert catastrophe. For years the clock displayed more mysterious kinds of time, though it always seemed to harbor doom. Time is as terrifying as it is beautiful. We can summon optimism or swim in pessimism. Sometimes we do both. I’m always impressed by those who maintain a steady sense of hope like Kate Bornstein.

I met Kate once. My friend was working at a trans nonprofit and she was trying to get Kate onboard for a project. Kate was busy with rehearsals for a play at the time but agreed to meet us at an old historic pizzeria in Harlem. We talked a little bit about our paths; I was fresh out of film school trying to make it in Brooklyn, my friend had gone to Oakland to work in the nonprofit sector. In some ways we’d chosen opposite paths.

When my friend went to the bathroom, Kate looked me straight in the eyes and warmly asked how I was doing. Her gaze was frightening, one of the few times in life when someone clearly sees through your flimsy facade and calls you on it. I was desperate to be successful, to make up for lost time. I don’t know what I muttered in reply but I’ll never forget what she told me. “Your life doesn’t have to be profound.”

I latched onto her words, even if they didn’t change my behavior. I fixated on the question she provoked. Why did I think my life had to be profound? There were plenty of structural reasons. I only did the things I felt I had to. The big things: get a job, move away from home, make art, go to therapy. I kept looking for big a-ha moments, refusing to create the little daily practices that make life worth living. Pleasure was the missing ingredient.

Survival doesn’t feel romantic. I’ve watched plenty of girls go in and out of the psych ward. I spent so much time in high school talking girls down, in the hopes someone would talk me down when I needed it myself. It’s annoying when mental health is reduced to simplistic John Green narratives. It’s easy to grow up and forget the way everything felt like life or death back then—and sometimes it was.

On a cold January night, sitting on the stoop with my friend, I asked if she considered herself a fundamentally optimistic person.

“Yes.” She paused. “Are you?”

“I think I’m a fundamentally pessimistic person,” I replied. I’m a romantic, but I’m not an optimist. Hope for the best, prepare for the worst, as they say. I engage with self-help and therapy because I do genuinely think they help, but I don’t think they erase the incredible violence around us.

I had my optimistic phase, I wanted to say. I thought the world would be welcoming, that capitalism could care, that poetry was enough, that Tarot was healing, that I would find the answer on a podcast. Even when I went through a brief cycle of optimism something inevitably tore the curtain. The doomsday clock in Union Square, the passing of a friend, seeing someone’s scars.

For a while I thought I was Carrie Bradshaw even if what I wrote at the time didn’t have half her wit. I kept dating gay men even when I knew they couldn’t place my body in their canon of desirability. I only felt a part of the fag family through the mediation of women.

Once in a sex shop with my friend A, a woman complimented my Keith Haring tote bag. “It’s good to see him in the city again,” she said. I felt overwhelmed by the bending of time and space.

Months later, at a mall, also with A, a man complimented the same bag and said he’d seen Keith only days earlier.

“He’s dead,” I said.

“What? No. I just saw him.”

“He’s dead,” I repeated.

“I don’t know, I saw him.”

“He’s dead, he died from AIDS.”

I want to walk away from the optimism-pessimism dialectic trap. I want to enter something beyond a good ghost story, slip on a slip dress, and not be asked for identification at the pronoun circle. I want to look into the eyes of every man whose ever underestimated me and sit on the back of a beautiful woman’s motorcycle. I do not want to be someone’s side project in the replication of beauty through martyrdom like Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane.

Except sometimes I do. Sometimes a ghost story is exactly what I need.

Keith Haring spent many years depicting heaven and hell in his work. His poptimistic icons bent into positions of ecstasy and terror, sucking and fucking, loving and hurting. There is not always the option to repair what is lost or, if there is, it’s often found in unexpected moments with loved ones and strangers. Ghosts ask for an audience, dancing under mushroom clouds with sexy devils.

When I was a fag I did as fags did. I had a friend take a picture of me at the Center in the Keith Haring mural room. It used to be a bathroom. Now it’s a room full of penis drawings. But with the right lighting and the right dress someone could slip their hand up my thigh and suggest we do something besides droll on about how apocalyptic our thinking has become. Some sexy devil could remind me the heaven that bathrooms can become.

Church Bulletin:

Since I haven’t done one of these in a very long time, forgive me for the length here. I wrote about Alex Graham’s graphic novel Dog Biscuits, a Cindy Sherman retrospective, nudity in contemporary art, and Issey Miyake’s required gallery-hopping uniform for Observer. For Xtra, I wrote about Greer Lankton and the archives cropping up to memorialize her work and spoke with the iconic Cecilia Gentili. Over on i-D I profiled the unpunishable Ethel Cain. At LARB I wrote about the state of the queer essay. I interviewed Irene Silt about process over at the Rumpus. If you’re a Study Hall subscriber I also wrote for their Digest. For the Baffler I wrote about a long-lost Katherine Dunn novel and the sad girl manifesto.

Finally, at Triangle House Review I have a very special short story I’ve been writing for a few years about a trans girl who sexts Satan while wandering around Florida.